While excellent newsletters on specific themes within public policy already exist, this thought letter is about frameworks, mental models, and key ideas that will hopefully help you think about any public policy problem in imaginative ways. Audio narration by Ad-Auris. If this post was forwarded to you and you liked it, consider subscribing. It’s free.

India Policy Watch: The Road Of FireInsights on burning policy issues in India- RSJ The Union Defence Minister along with the chiefs of the three armed services on Tuesday announced the ‘Agnipath’ scheme for recruitment into the Indian military. You can read more about the scheme here. I have summarised the key features below:

The government also positioned this as a move that will infuse youth and vitality (or ‘josh’ and ‘jazba’ as mentioned in various media reports) into the armed forces. The whole thing including the names Agnipath and Agniveer sounds like a campaign for an early 1990s Nana Patekar film. You could soon shoehorn Agni Pariksha (for the recruitment tests), Krantiveer (best Agniveer cadet), Yugpurush (lifetime achievement award for Agniveers), Angaar, Tiranga, Prahaar and so on. You get the picture. We are in this territory now. Anyway, the average age of the armed forces which is 32 now will come down by about five years. The younger workforce will be more technology-savvy that will be more attuned to the changing nature of modern warfare. Also, the 75 per cent of Agniveers who will go back into civil society will serve as a disciplined and nationalistic labour pool to draw from for organisations. There will be Agniveers in every village and taluk who will improve the moral fibre of our society. We will have no riots, no littering, no traffic violations and no crime. The retired Agniveers will change us. Because they will put the nation first. Always. Like Arnab. Well, that’s the official line anyway. BacklashUnfortunately, the response to the scheme hasn’t been what the government was expecting. There have been protests, arson and general lawlessness by unemployed youth that seems to be spreading across the country at the moment. A large section of retired armed forces officials too have questioned both the scale and speed of a change like this. The issues agitating them have some basis:

These arguments, for and against aside, this is a good example to understand the complexities of policymaking, especially in defence, in India. A Difficult ProblemLet’s begin with the single most important policy objective for armed forces now in India. This is quite stark and apparent - it needs to modernise its defence infrastructure and increase its capacity in areas of modern warfare like the air force and navy. Given the threat perception on its borders, this is an already delayed exercise. You can read a detailed ORF report on India’s platform modernisation deficit here for more. TL;DR: yes, we do have a modernisation challenge on hand. And it is quite bad. Now the key question is what’s coming in the way of modernisation? There are multiple answers to this but on the top of that list is a lack of funds. The defence budget has broadly remained around 2.2 per cent of the GDP over the last decade. India has struggled to contain its fiscal deficit and it has limited ability to allocate more to its defence budget. As we have written on umpteen occasions, the Indian state is spread wide and thin. It does way too many things badly. Therefore, it cannot find money to do things it must. More importantly, pension benefits (24 per cent) and wages (28 per cent) take up over half of its budget. These numbers, especially pension outlays, will continue to grow in the coming years as the full impact of OROP (one rank one pension) plays out. The OROP that came into effect in late 2015 is a known and acknowledged policy mistake that is quite simply unsustainable. But it is almost impossible to walk back on that now. So, the search for circumventing that burden is one of the factors that has led to this scheme. A bad policy decision has a long-term downstream impact and this is a classic case of that playing out. Even if the Agnipath scheme is implemented as it stands today, the easing up of the pension burden will take decades to play out. The need for modernisation of the armed forces is as of yesterday. But the government is hoping through a combination of a 10-15 per cent reduction in the strength of the military and a long-term solution to control the burgeoning pension bill would have given it some room to ramp up on modernisation without increasing defence outlay. There are various estimates of the net present value of the expenditure on a single soldier who joins the armed forces today. At fairly conservative estimates of discount rates, wages and future pension benefits, Pranay estimates this to be about INR 1 crore. In my view, that is the absolute floor for that value and it might be around INR 2 crores if one were to take a bit more realistic assumptions. So, a 1.5 - 2 Lac workforce reduction could mean a significant availability of funds to modernise the defence platforms over time. Growth, Growth, GrowthThat’s likely the thinking that’s gone behind the scheme. Everything else including the messaging on josh and jazba or having retired Agniveers in every village is to make it palatable to the public. It is difficult to acknowledge openly to people that the economy cannot support the defence requirements of India when you have made nationalism and nation-first important planks of your political strategy. This communication plan could have worked except it had to contend with the other real problem of the Indian economy at the moment. Lack of jobs. For reasons that could take up another post, the Indian economy isn’t generating enough jobs for its large youthful population. Roughly, India needs to create between 15-20 million non-farm jobs every year to keep pace with those entering the labour force. The labour participation rate has remained in the 40-45 per cent range for a long time. New job creation data can be contentious but it is difficult to argue that India is creating anything more than 3-4 million jobs every year. The quality of many of these new jobs isn’t great. The merry-go-round of employees switching jobs and getting big hikes in the IT/ITES sector shouldn’t blind us to the reality in the broader economy. There aren’t enough jobs. The two prerequisites for job creation, an 8-9 per cent GDP growth and skew towards sectors like construction, infrastructure or labour-intensive exports aren’t being met. The reason the job crisis hasn’t snowballed into a larger political and social issue is the immense faith in the PM among the youth. There’s a strong belief among them that India is on its way to becoming a superpower. The regular dose of nationalism and jingoism that’s amplified by the media helps continue this narrative. A related issue here that accounts for the violent protests is the lure of government jobs. The public sector jobs at the junior levels have become more remunerative than similar roles in the private sector in the last decade. As much as people love quoting the salaries of the CMDs of PSU Banks or the senior IAS officers and comparing them to the compensation of private-sector CEOs, the reality is that at mid to junior levels the government jobs are better paying. You can dig deeper into the wage bills of listed PSUs and compare them with their private counterparts for evidence. The other supposed benefits of a government job like job security, work-life balance and a possibility of rent-seeking (though low in defence jobs) make the package very attractive. This has meant a dramatic reversion in trend of people hankering for public sector jobs that had waned in the first couple of decades of liberalisation. So, a reduction in the number of such jobs or cutting down their benefits as the Agnipath scheme is likely to be isn't going to be accepted despite the great popularity of the PM and the ruling party among this segment. Their expectation, in contrast, is for the number of government jobs to go up. Considering the constraints, it is difficult to see what else the government could have done here. The need to reduce wage and pension costs to fund modernisation is real. And given the fiscally conservative instinct of this government, it won’t deficit fund the modernisation programme. As is its wont, it has chosen to put a bold announcement with emphasis on other benefits while trying to solve its key problems under cover. There’s this myth that a big bang approach to reform is the only model that works in India. That’s wrong. A lot of what has looked like big reforms in India have actually had a long runway that’s often invisible to people. A more comprehensive reading of the history of ‘91 reforms makes this clear. So, the usual template has been followed so far: minimal consultation, no plans to test it out at a smaller scale and instant big bang implementation. The results are unsurprising. I am guessing we will see a similar script play out for the next few months. There will be rollbacks (a few have been already announced), some concessions that will tinker around years of service or percentage releases, and a few sops thrown in, to temper the anger. If I were to give more credit than is due to this government’s planning chops, I might even say it possibly did this on purpose. Release a more extreme form of scheme, brace for impact and then roll back to the position that you always wanted in the first place. It is one way to game public opinion to your favoured outcome. Of course, a more impactful solution to this is to acknowledge the mistake that OROP is and shift the pension of defence forces onto a voluntary, defined contribution scheme like the NPS which has been implemented since 2004 for all new recruits joining government services, except defence. That is the only sustainable solution to this problem. But dispassionate policy making in defence sector in India is difficult. All kinds of emotions about izzat, vardi, naam and nishaan get mixed up. Nana Patekar gets in the way of clear-headed thinking.

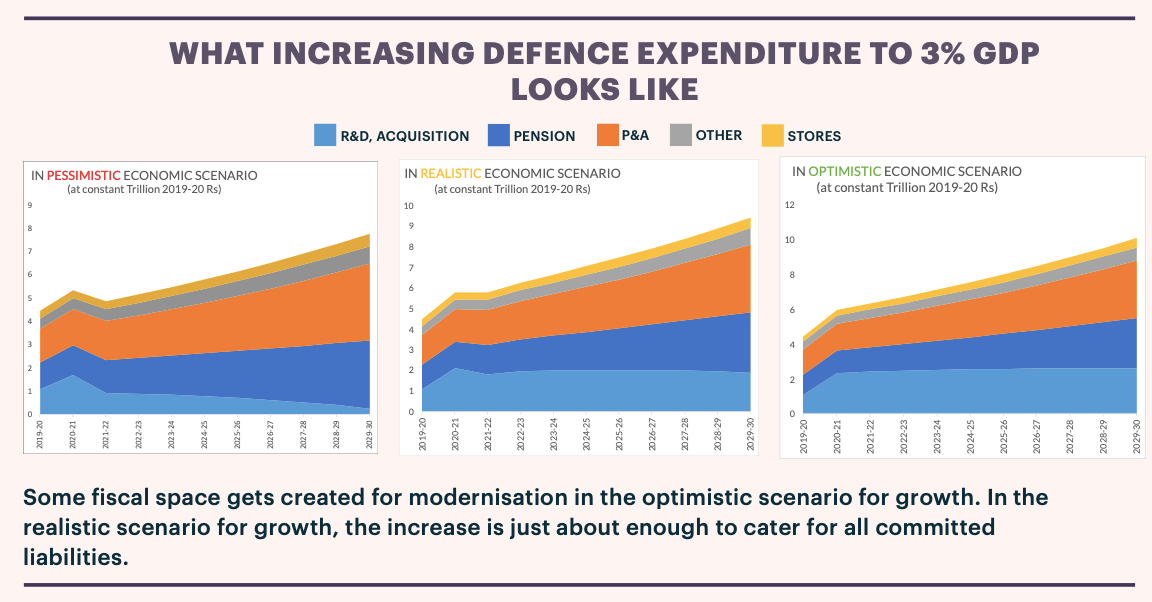

* (with apologies and acknowledgement to Harivansh Rai ‘Bachchan’) Addendum— Pranay Kotasthane For a researcher working on the public finance of defence, the Agnipath scheme is an important milestone. Over the long term, it has the potential to substantially reduce the pension burden. And as RSJ writes, the scheme will have no impact on the allocations for modernisation in the short term. Nevertheless, this scheme is important for the single reason that just as today’s deficits are tomorrow’s taxes, today’s reforms become tomorrow’s savings. Many commentators suggest that India’s defence expenditure problem can be solved merely by increasing defence expenditure to 3 per cent of GDP, from the current allocation of 2.04 per cent. That’s hardly the case. Projecting current growth rates of defence spending components over the next ten years suggests that even if the government were to agree to a 3 per cent spending, pension spending will grow rapidly enough to allow only an incremental increase in the fiscal space for capital outlay. Keeping the public finance angle aside, I took away two lessons in politics. One, the political narrative that can be used to sell a policy solution sometimes matters more than the solution itself. In an article for the Times of India in March, I listed four alternatives before the government to manage personnel costs. The three solutions that were dropped tried to address the pension problem directly. It wasn’t possible to project these solutions as achieving any other objective. In contrast, the solution that was picked up, i.e. Agnipath, was the only one that allowed the government to skirt the fiscal motivations for this reform. The government went in with this stated objective: “attracting young talent from the society who are more in tune with contemporary technological trends and plough back skilled, disciplined and motivated manpower into the society.” No mention of the fiscal angle. At all. This strategy itself had mixed results in the early days. Politically, it allowed the government to make statements such as these:

However, not acknowledging the real reason why these reforms were mooted, created an impression that the government has needlessly and suddenly foisted another disruptive scheme on unsuspecting masses. Two, the government failed to align cognitive maps of important stakeholders, yet again. Pension reforms are wicked problems everywhere in the world because there are strong endowment effects of a large, organised collective at play. Some of you might recall that a couple of years ago, nearly 800,000 French people protested and disrupted key services across the country in opposition to the proposed pension reform. That reform merely aimed to consolidate 42 different pension schemes, with variations in retirement age and benefits, into a universal points-based system. Even so, the government had an excellent, indigenous pension reform example at hand. As we’ve written many times before, the civil services pension reform of 2004 was a rare example of introducing a scheme to reduce the pension burden without protests. Despite this example, the government chose to opt for an Agnipath scheme that made some applicants suddenly ineligible for selection. The resulting protests and violence eventually made the government relax the age criteria this time. The government mandarins would surely have anticipated these consequences. To smoothen the transition, the government could’ve done regular recruitment along with the Agnipath recruitment this year. Over the subsequent three-four years, it could have increased the intake for the latter and tapered down the intake in the regular induction in a phase-wise manner. But it chose a sledgehammer instead of a scalpel. Global Policy Watch: Social Media’s Rule of ThreeGlobal policy issues relevant to India— Pranay Kotasthane Social media continues to confound us all. By now, we all have read a number of hypotheses on how social media rewards “evil”. In the initial days, social media’s tendency to push us into echo chambers was oft-cited as the mechanism that made people more extreme in their views. Then came the view that the evil lay in the “likes”, “retweets”, and “share” features, which promoted an asymmetric virality. Thereafter came the notion that it was the economic models that were to blame. Advertisement-led services and Big Tech monopolies were the real problems, we were told. And over the last four years or so, it’s the algorithms and recommendation engines of social media companies that have been the target. Despite these arguments, we still don’t have a conclusive answer. Several studies have refuted many of the assertions made above. And so, let’s take a step back from specific social media apps, and instead ask: what are the meta-mechanisms that make all forms of social media a powerful instrument? I can think of three interrelated mechanisms. All three mechanisms are connected to sociological and cognitive behaviours in the Information Age. One, Social Media expands our Reference NetworksReference Networks is a term used by psychologists to mean “people whose beliefs and behaviour matter for our behaviour”. A really small part of our behaviour is independent of others’ actions and beliefs. Most of our behaviour is interdependent, i.e. it depends on what people in our reference network say or do. For most of human history, geographic proximity largely determined our reference network. For instance, our on-road driving behaviour is shaped by people who are around us and whom we consider ‘like us’. TV, radio, books, and newspapers have played a major role in creating new horizontal comradeship (or what Benedict Anderson called ‘imagined communities’), but these media did not supplant the importance of geographically proximate reference networks. Social media, by contrast, expands our reference networks like never before. People across the world can now influence our perceptions instantly and repeatedly. And by this reference network expansion, I do not imply the ‘echo chambers’ trope. Courtesy of social media, our reference network in fact now includes many more people who think unlike us. Sociologist Zeynep Tufecki explains this mechanism using a beautiful metaphor:

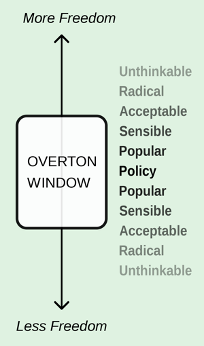

Expressed another way, every issue becomes global by default because our reference networks are also global. Two, Social Media expands the Overton WindowRepeating what I had written about this particular mechanism in edition #130.

With the old gatekeepers no longer wielding the same power as earlier, the range of opinions on any issue can be extremely broad. And combined with the fact that each of those views attracts a new reference network, the Overton Window of social acceptability gets stretched. Three, Disproportional Rewards for Extreme ContentMany analysts say that this mechanism is a result of skewed algorithms and the incentives arising out of an advertisement-based model. While that’s partly true, there’s a deeper reason: information overload. Persuasion is a key power in the information age. Persuading someone requires attracting someone’s attention. And since attention is a scarce commodity in a crowded information environment, the only way to attract it is to come up with something surprising and shocking. Consider this analogous example. If I were to write “Lng Yrs g, W Md Tryst WTh Dstny”, you would immediately identify that I’m talking about Nehru’s iconic 1947 speech, despite me dropping all vowels. From an information theory perspective, vowels carry “less” information content because they occur more frequently. In contrast, consonants contain “more” information because the probability of their occurrence is low. In a similar manner, a news feed post which reads “There was a bomb blast in Kabul”, carries less information, because this has quite unfortunately become a regular occurrence over the last few years. In contrast, a shocking opinion or news like “Russian information ops influenced the 2016 election results” surprises us, and hence carries more information. Over time, not only does the Overton Window expand, it becomes broader at the two poles. My proposition is that many real-life events attributed to social media (positive or negative) can be explained by a combination of these three mechanisms. Consider the work done by an online group DRASTIC (Decentralized Radical Autonomous Search Team Investigating COVID-19) in mid-2021. Their work alone changed the conversation on the Wuhan lab origin theory (RSJ wrote about it here). In this case, the expanded reference network allowed a band of interested folks to build on each other’s work. The Overton Window expansion meant that the group could put forward an idea that seemed preposterous at that time. And a skew towards surprises meant that their idea didn’t just die away in a closed in-group, but instead sailed across the globe. HomeWorkReading and listening recommendations on public policy matters

If you liked this post from Anticipating The Unintended, please spread the word. :) Our top 5 editions thus far: | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||