Soft Fruit and Hard LabourStrawberry picking and the long history of seasonal farm work. Words by Rees Nicolas. Illustration by Sinjin Li.Good morning and welcome to Vittles. All contributors to Vittles are paid: the base rate this season is £800 for writers (or 40p per word for smaller contributions) and £300 for illustrators. This is all made possible through user donations. A Vittles subscription costs £5/month or £45/year ─ if you’ve been enjoying the writing then please consider subscribing to keep it running and keep contributors paid. This will also give you access to the past two years of paywalled articles, which you can read on the Vittles back catalogue. If you wish to receive the Monday newsletter for free weekly, or to also recieve Vittles Recipes on Wednesday and Vittles Restaurants on Friday for £5 a month, please subscribe below.

Soft Fruit and Hard Labour: the long history of seasonal farm workWords by Rees Nicolas, Illustration by Sinjin Li. 1. Nomad harvesters Ours is a land of nomad harvesters, Marie De L. Welch, ‘The Nomad Harvesters’ In June, on what was the first really hot day of summer, I walked into my nearest Sainsbury’s and bought a punnet of strawberries. Neatly printed on the packet’s film lid was a label explaining that the strawberries had travelled a short distance up the A2 from Kent, and naming their producer as Sean Charlton. But what does that mean? Sean Charlton is the director of Charlton Farms which, according to their website, produces 5,000-6,000 tonnes of strawberries a year and has an annual turnover of £61 million. Behind the brand are hundreds of seasonal workers, nearly all of them migrants on short-term visas. The importance of these nomad harvesters for British horticulture, and strawberries in particular, cannot be overstated. British Berry Growers, the industry body representing berry farmers, estimates that their members employ around 45% of all seasonal labourers in the UK. On an average strawberry farm, the number of workers rises between three and five times during picking season; Charlton Farms, where a range of soft and top fruit is grown, employs 650 people in the winter and 1,400 in the summer. Under the surface placidity of agricultural life is a teeming factory in the fields, equipped with barracks of caravans and temporary accommodation, computerised glasshouses and polytunnels, capital-intensive machinery and state-of-the-art packing houses. Back in February of this year, British Berry Growers had reason to feel triumphant. At the National Farmers Union annual conference, Mark Spencer, the Minister of State for Food, Farming and Fisheries, made a speech referring to migrant workers brought to the UK as part of the Seasonal Agricultural Workers Scheme (SAWS), which was introduced after Brexit to mitigate the loss of farm labour from the EU. Spencer said:

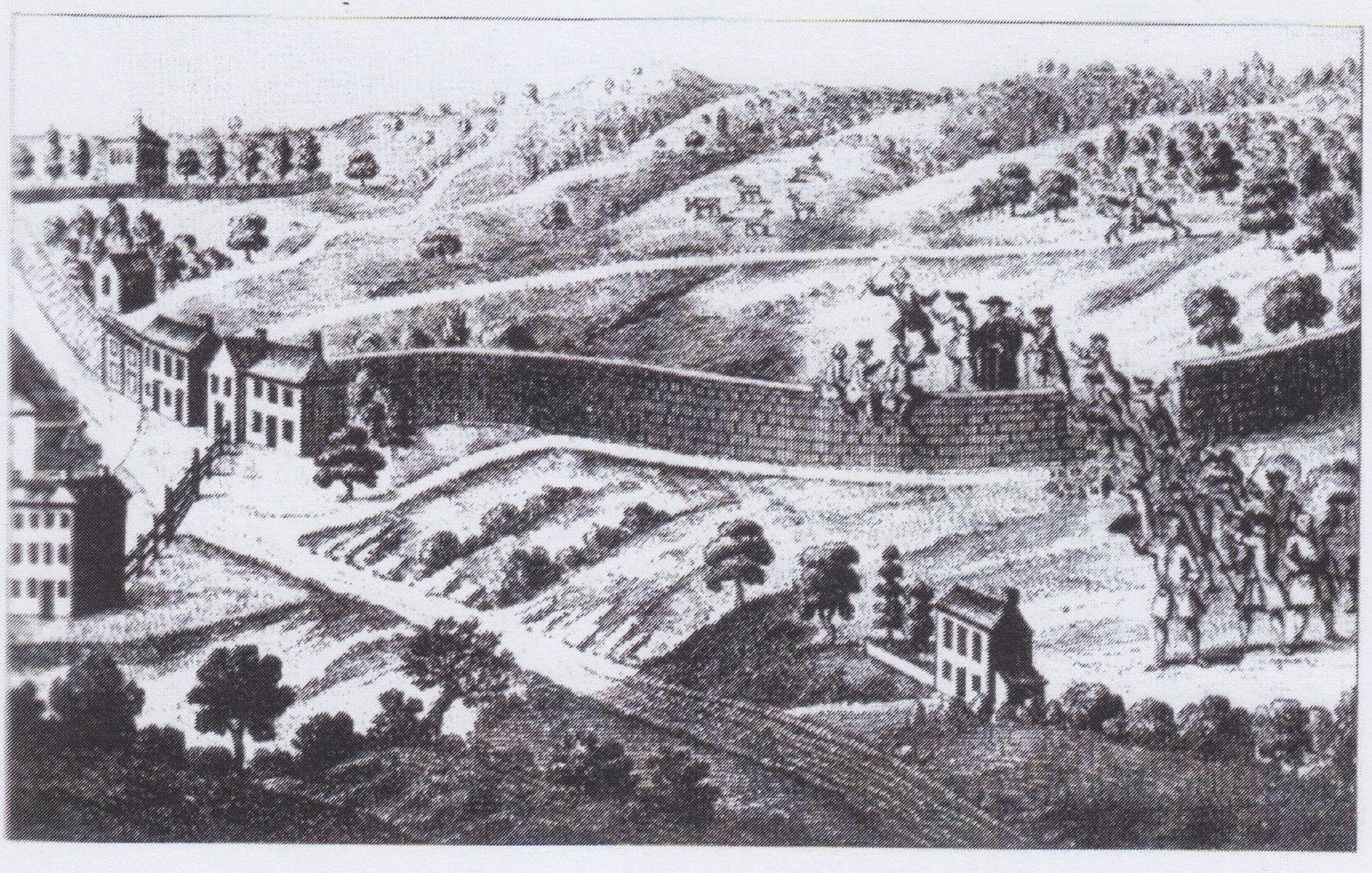

Observers unfamiliar with the agricultural labour market might have interpreted the offer of a living wage for migrant workers as an overt challenge to farmers, whose chief priority was lowering labour costs. However, business-owning farmers heard something different in Spencer’s words: an admission of defeat. The year before, in 2022, they had been outraged by the government’s decision to set the minimum wage for the seasonal labourers harvesting their crops at £10.10 – equal to the pay of workers given visas through the Skilled Worker Route, but 60p above the National Living Wage. Farmers complained that it represented an increase of 13.5% in their labour costs, that it would reduce overall production, that it would put them out of business. So in February Spencer was actually announcing a relative reduction of wages for seasonal workers, assuaging the anxieties of the rural capitalist class – the most anxious of whom were the strawberry farmers, whose businesses rely entirely on low-paid seasonal migrant workers. In one sense, farmers’ reliance on migrant seasonal workers is a novel situation. As recently as 1998, 95% of seasonal labour in some parts of England was still performed by domestic workers – largely locals and extended family. With the expansion of the EU in the 2000s, this changed. Farmers looked to new member states, Romania and Bulgaria first among them, for workers who would accept lower wages; their fear of unemployment and deportation made discipline easier to impose. They were aided in this by the government’s decision to expand its quota of seasonal European agricultural workers from 5,000 in the early 1990s to 25,000 in 2004. Today’s SAWS draws its labour from a staggering array of countries. In 2019 Ukraine provided 91% of workers, but as the war with Russia has dragged on, recruitment operators have begun to find workers further afield – in Central Asia, Moldova, South Africa, Nepal, and Indonesia. And while this legal framework – created by parliament to supply farmers with a market of workers whose origins are outside the land they farm – may seem like a recent phenomenon, in another sense it is one of the original features of British agrarian capitalism, which began centuries ago. 2. Dispossess the swain A time there was, ere England’s griefs began, Oliver Goldsmith, ‘The Deserted Village’ In The Origins of Modern Capitalism, the historian Ellen Meiksins Wood argues that modern capitalism was born ‘not in the city but in the countryside,’ in sixteenth-century rural England. For Meiksins Wood it is not the exchange of a commodity for money in a marketplace that defines the emergence of capitalism, but the ‘complete dispossession of the direct producers’. Peasants who had previously survived through subsistence farming were forced into becoming workers, exchanging their time for a wage in order to ensure a ready supply of labour for England’s new agrarian capitalist class. Food was transformed into something you bought with your wage, not the thing you produced for yourself before selling any excess to someone else. The original act of agrarian capitalism was to divorce labourers from the land they worked. The disciplining of workers through dispossession was accomplished through the systematic enclosure of common land over several hundred years, beginning in the sixteenth century. Commons – land shared by a community to meet their collective needs according to a set of agreed rules, which had previously offered people a place to grow crops, gather firewood and raise livestock – were to be privatised. This process reached its apogee in the eighteenth century: between 1760 and 1870 around one-sixth of the area of England was enclosed through 4,000 acts of parliament and the incessant brute force of the landowning class. These commons were placed in the hands of a few rich landowners, who turned them into the forerunners of today’s large-scale agro-businesses. Once enclosure had forced commoners into the labour market, it was important for landowners not to provide rural workers new forms of self-reliant subsistence. One reason England’s many rural hedgerows are so devoid of flavour to this day is that when they were first planted farmers were worried that ‘the idle among the poor … would still be less inclined to work, if every hedge furnished the means of support’ (as Thomas Rudge writes in his 1807 A General View of the Agriculture of the County of Gloucester). The idyllic fantasy of rural England that frames many a party-political broadcast is really a living record of historical class conflict and state intervention. As ever-greater numbers of people were thrown off the land to supply labour to the farmer, the rural population began to empty out of the countryside and migrate to the growing cities, and so shortages in agricultural labour ironically became more pronounced, requiring new systems of seasonal migration to supply the deficit. One ready source came from Ireland, where similarly dispossessed rural populations had, since the eighteenth century, travelled in large groups to England. Alongside the Irish were groups of internal migrants who travelled smaller distances between villages or across county lines. This practice developed into what became known as the ‘gang system’, and similarly arose from the demands of agrarian capital and the policy of the state. The root of ganging lay in the distinction between ‘open’ and ‘close’ parishes in rural England: the 1601 Poor Relief Act laid foundations for the next 200 years of unemployment and disability benefit, crucially putting the burden for financing relief on the individual parish in which the poor person lived. Then, in 1662, a further act of parliament specified that the parish in which the person was born should pay to support them. This incentivised landlords to evict their farmhands and instead import labourers from other parishes, knowing they would not be responsible for supporting them financially and could send them packing once the work was accomplished. ‘Open’ parishes were those in which dispossessed labourers could freely settle and from which they then migrated to work elsewhere; ‘close’ parishes were those whose populations were tightly controlled by the landowning class to ensure they did not have to pay to support their working population in times of ill health or unemployment. As enclosure led to the enlargement and consolidation of estates owned by ‘territorial aristocrats’, increasing numbers of workers from ‘open’ parishes were recruited to work for their ‘close’ neighbours, performing seasonal and occasional labour on large, arable farms. Eventually these groups of internal migrant labourers – mostly women and children – were organised into ‘gangs’ and employed on a collective day rate. They would frequently walk as many as ten miles to work, and were subjected to the harsh discipline of a ‘gangmaster’ – part-supervisor, part-recruiter, known for being ‘a bad lot, a rake, unsteady, drunken, but with a dash of enterprise and savoir-faire’. By the middle of the nineteenth century the exploitative cruelty of the gang system had become a national scandal, and was linked to everything from increased infant mortality to alcoholism, so-called bastard children and dissolute women. Finally, in 1867, the Agricultural Gangs Act regulated the market in gang labour for the first time and specified that gangmasters had to be licensed. 3. To gather strawberries all day long He told of girls – a happy rout! William Wordsworth, ‘Ruth’ If any of this account of the gang system sounds familiar, that’s because it was the precursor to the modern SAWS. Just as tenant farmers in close parishes had exploited travelling gangs – knowing that they owed alien labourers fewer rights, were not subject to the moral requirements of loving their village neighbour, and could dispose of them more easily – so today’s strawberry farmers indirectly hire pickers from Nepal and Indonesia through faceless recruitment operators and dubious third parties, knowing that debt, strict visa rules, and limited government oversight all combine to ensure a more pliable, motivated, and disciplined workforce than could be found in the domestic labour market. How, then, does this affect the strawberries in my punnet? In Strawberry Fields, a ground-breaking study of agricultural labour in the California strawberry industry, Miriam Wells showed how the particular characteristics of strawberries had shaped and reshaped the nature of the work itself. I would argue that the inverse has also been true in the development of the British strawberry industry: the particular characteristics of the work have reshaped the nature of the strawberry. For the modern strawberry farmer, the first priority is the picking of the largest number of strawberries with the least amount of labour. A heated market has emerged in which research businesses such as the East Malling institute compete to breed the most pickable strawberry, the strawberry that will cost the least to pick. Plants are bred to produce higher yields, increasing the quantity of strawberries produced over the same surface area and the speed at which a punnet is filled. In the 1920s, yield was around 2 tonnes per acre, and today it is closer to 30 tonnes per acre, with some farmers pushing 35 tonnes. Similarly, a decade ago the average strawberry was about the size of a pound coin, today they are closer to golf balls. The reason for this change is that larger strawberries mean less work is needed to fill each punnet. Strawberries have also become firmer, ensuring that labourers are able to pick them more quickly and with less sensitivity, that they are less likely to degrade on the journey between farm and packing plant, and that fewer punnets will be turned away by supermarkets for damaged or imperfect product. And so, while larger, firmer strawberries – whose plants produce greater quantities – are notoriously less flavourful, their higher yields, reduction in labour costs, and adaptability to transportation make that a price worth paying for strawberry farmers. And of course, as the per-unit labour requirement of each strawberry has gone down, the amount of labour required per labourer has gone up, with workers during the peak season often complaining of being made to start work before the sun has risen and finishing long after it has set. Strawberries are also now almost exclusively grown inside polytunnels or greenhouses, meaning that weather fluctuations have less impact on the plants. In 2019 Charlton Farms invested £5 million in retractable greenhouses designed to adapt in real time to climactic conditions. In April of this year, Charlton Farms also received planning permission to erect 16 acres of greenhouses in Hempnall, Norfolk. The chair of the local parish council, David Hook, complained that ‘it [would] transform green fields into what is essentially an industrial site’. In defence of the scheme, Sean Charlton argued that the extra crops would not require any extra workers, because the modern greenhouses would increase efficiency. Inside these greenhouses, plants will not grow in soil but in containers of specially prepared substrate. Nor are they to be found planted at ground level; instead, they are placed on tabletops, ensuring workers no longer need to bend down each time they pick a berry – saving time, reducing sickness absences, and increasing productivity. Finally, growers have increasingly opted to plant ‘day-neutral’ (as opposed to ‘short-day’) varieties of strawberry, leading to consistent production over a longer period of time and extending the strawberry season from 6 weeks in the 1990s to close to 9 months today. Strawberries are no longer the seasonal fruit they once were, nor are they as rare: soft fruit production has risen 600% in the last 25 years, and the UK now produces 120,000 tonnes of strawberries alone. This change to the strawberry season has also led the NFU to push for the Seasonal Worker Visa to be extended from 6 to 9 months, offering farmers a near-constant supply of poorly paid, vulnerable, and therefore easily disciplined workers. At the same time that migrant workers become increasingly central to the UK food economy, there has been chest-thumping from nationalist politicians about the need to reign in the scheme and replace migrant labour with British labour. The government has fruitlessly looked to enact policies that will negate the need for it. The ‘Pick for Britain’ scheme, launched at the start of the Coronavirus pandemic, almost immediately descended into farce, failing to deliver even a fraction of the local labour it had promised. Some farmers have put their hope in automation, but while capable of weighing, labelling and moving pre-packed punnets, machines are still far too clumsy to replicate the skill of an experienced strawberry picker. And despite Mark Spencer’s plan that SAWS will help ‘mind the gap’ until automation has developed sufficiently, his department’s own review of automation in horticulture last summer admitted that ‘it is unlikely the current crop varieties, growing architectures and infrastructure are optimal for automation and robotics.’ In practice, there has been little interest in anything other than the yearly renewal of SAWS. In every year since the scheme was founded in 2019, the government has increased the number of visas offered, in large part because farmers now say they cannot do without them. Farmers themselves point out that the squeezed prices they receive for soft fruit, as a result of supermarkets’ total control over produce in the UK, mean that they would never have the capital needed to invest in automated fields, even if it were practically possible. Simply put: without a seismic transformation of fruit biology, industry, supermarkets, the environment, and the labour market, migrant agricultural labour is going nowhere. 4. Fences are broken But fences are broken, Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional, ‘Tomorrow begins today’ Where food is produced as a commodity, there will be a division between those who produce and those who own the product of their labour, those who work the land and those who possess it. In this situation, migration will continue to be necessary. Migration, far from a novel or extraneous development, is foundational to an agricultural system geared towards expropriation and profit. Like the residents of ‘open’ parishes before them, seasonal agricultural labourers operate as a non-citizen labour source intentionally alienated from certain economic and social rights, making them super-exploitable and disposable. Where once the dispossessed ‘swain’ might have travelled a handful of miles – down from the Highlands, or across the Irish Sea – to work someone else’s land, today’s labour market drags them halfway across the world, demanding they invest thousands of pounds in application fees and travel costs before they even step foot in the field, and then disqualifying them from the benefits of their labour as soon as the season is over. Migrant labourers from every nationality working on British farms complain of conditions akin to slavery. At a time when borders continue to be reinforced and intensified in Britain and around the world, any struggle for justice in the fields continues to lie in the breaking of fences. Historically, the demand put forward by the agrarian working class has been for land reform, the redistribution among workers and tenants of large tracts of land held by a few wealthy ‘territorial aristocrats’ (the term W.G. Hoskins uses to describe the emergent large-scale landowner of agrarian capitalism in The Making of the English Landscape). The breaking of these fences is undoubtedly crucial, but when so much of agricultural labour is performed by migrant workers who come and go with the seasons, it can only be meaningful if accompanied with a breaking of the fence dividing citizen from non-citizen. Where a two-tier workforce exists, it will be used to exploit migrant labour and differentiate between classes of worker – to the detriment of citizen and migrant alike. To undo this situation, seasonal migrant workers must have the same right to change job and refuse work, to benefits and legal recourse. SAWS visas must be unconditional, meaning that they only expire at the end of a set period, stopping employers or recruitment operators from using the threat of deportation and debt to silence workers expressing concerns about mistreatment or exploitation. It is also incumbent on organised labour to support initiatives such as The Landworkers’ Alliance and the Farmworkers’ Solidarity Network, which seek to facilitate the organisation of migrant agricultural workers. In the retail and hospitality sectors, workers and unions should seek to support workers’ rights and struggles further up the supply chain. Consumers must also be willing to challenge the supermarkets’ monopsony, not by ‘buying ethically’ but by organising targeted boycotts and pickets of companies that directly and indirectly benefit from separating workers from the fruits of their labour. Fences have been broken before and they will be broken again; in every house, in every countryside, in every city. Credits

You're currently a free subscriber to Vittles . For the full experience, upgrade your subscription. |