While excellent newsletters on specific themes within public policy already exist, this thought letter is about frameworks, mental models, and key ideas that will hopefully help you think about any public policy problem in imaginative ways. Audio narration by Ad-Auris. If this post was forwarded to you and you liked it, consider subscribing. It’s free.

India Policy Watch #1: The Anatomy of DecentralisationInsights on topical policy issues in India— Pranay Kotasthane The human-made floods in some parts of Bengaluru generated much furore. Writing about it in our previous edition, RSJ remarked:

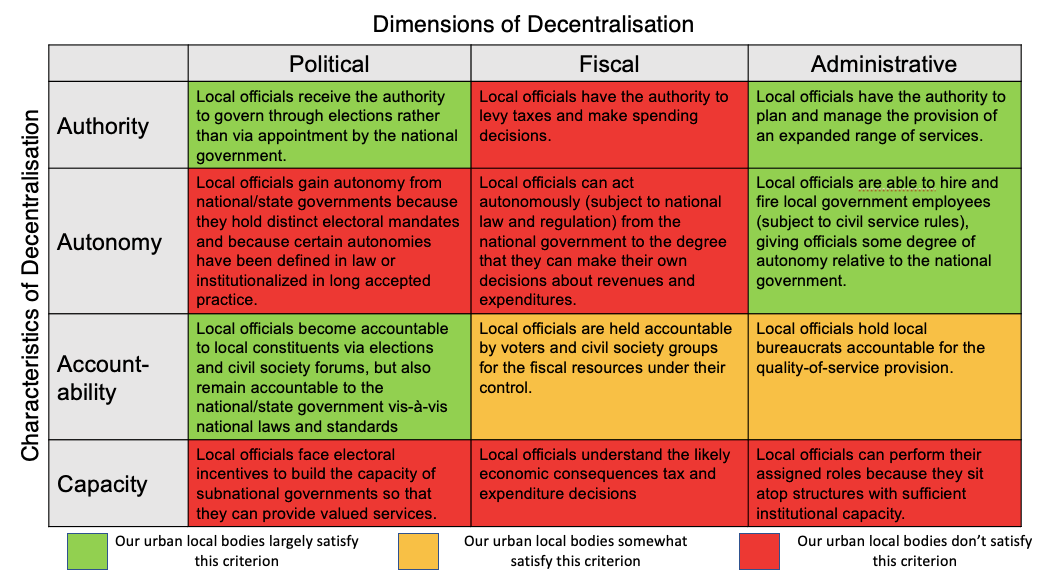

I share his anguish. However, I remain hopeful because there are many global examples of cities first committing themselves to and then rescuing themselves from the tyranny of half-hearted decentralisation. Decentralisation: Take 1The term decentralisation is a catch-all term in public policy. There was a time when it was touted as the solution to all ills. But many PhD dissertations, journal papers, and World Bank projects later, we understand it better now. Throwing some light on this concept can help us put a finger on what’s exactly wrong with Indian cities. Let’s begin by understanding the three forms of decentralisation — deconcentration, delegation, and devolution. Deconcentration is the simplest form of decentralisation. As the name suggests, it means decentralising functions and responsibilities. For example, if you can submit a passport application in Mysuru instead of having to come to the state capital, this function can be said to have been deconcentrated. The various government branch offices and grievance centre kiosks are examples of deconcentration. Delegation means that specific functions are carried out by another organisation or the government nearest to the citizen on behalf of the more distant government. In the Indian case, the plethora of state public sector enterprises (SPSEs) for public transport, power distribution, and water distribution are examples of delegation. For example, BESCOM is a Government of Karnataka company tasked with the responsibility of supplying electricity to the state capital. Devolution is the most comprehensive form of decentralisation. Devolved units hold defined spheres of autonomous action. Policy implementation and authority shift to the government nearer to the citizen. This typically means having elections at the subnational level. For example, Indian states are devolved units with clearly defined responsibilities, and tax revenue handles in the Constitution. With these definitions at hand, we have one way to diagnose the dismal performance of our city governments: the Union-State government relationship is characterised by devolution, while the State-local government relation is characterised by delegation and deconcentration. Elections do take place at local government levels. After the 74th Amendment in 1992, some more functions were devolved to urban local bodies. And yet, they hardly enjoy autonomy and authority in any defined sphere. State governments tightly control resources, personnel and plans, treating local governments as deconcentrated implementing agencies. Decentralisation: Take 2There’s another way to see the Indian experience in light of decentralisation theories. Decentralisation can happen along three dimensions — political, administrative, and fiscal. These dimensions are further characterised by four factors: authority, autonomy, accountability, and capacity. The USAID Democratic Decentralisation Programming Handbook has a helpful framework that combines these three dimensions and four characteristics. In the chart below, here’s how I think India’s urban governments fare on the twelve parameters at their intersection.

My crude classification into three categories is subjective and based on my understanding of local government public finances. Even so, this framework can offer valuable insights into India’s urban governments. First, they are characterised by poor capacity across all three dimensions of decentralisation. Hardly surprising. But here’s something more interesting: urban governments in India do pretty okay on administrative decentralisation, not so well along the political dimension, but score a big zero on the fiscal dimension. Devesh Kapur writes, “At the heart of state-building is a fiscal story”. And so, it’s not unexpected that the sorry state of fiscal decentralisation is a powerful reason behind the abject failure of our urban governments. The Way AheadAnd so, to fix our cities, we need energy and focus on improving along the fiscal decentralisation dimension. And how exactly do we get there? In this talk below, organised by the Bengaluru Navanirmana Party, I propose a few ideas for the Bengaluru government:

India Policy Watch #2: This Moment is PreciousInsights on topical policy issues in India— RSJ The more perceptive among you, dear readers, might have espied a certain pattern in my posts over the past six months. On the one hand, my tone has been steadily bullish on the medium-term prospects of the Indian economy. Almost four months back, in edition #168, I concluded that the then-nascent Ukraine war and the inflation roiling the developed world have put India in a sweet spot among global economies. I wrote:

Then in edition #182 (Aisa Mauka Phir Kahan Milega?), I sort of doubled down on this:

In the past couple of weeks, there has been a flurry of reports from global research firms echoing the same sentiments. IMF, usually the last to know what’s happening around the world, also seems to have cottoned on to this trend. This week its chief Kristalina Georgieva said that “despite global uncertainty and headwinds, India continues to be a bright spot in the global economy.” The proximate reasons are evident all around. Domestic demand is strong, inflation isn’t the runaway kind, the bank balance sheets are stronger and cleaner than ever, and we seem to be seeing off the peak of the commodity cycle. The other large emerging markets have their own troubles. South America is in the throes of one of its ‘how to shoot yourselves in the foot’ scenarios. Brazil is going through its most fractious election campaign ever, with the hard-left rhetoric of Lula seemingly ahead of Bolsonaro. That’s been enough for Bolsonaro to again take a leaf out of Trump’s playbook and raise doubts about the integrity of the electoral process. Venezuela has a Hugo Chavez bhakt running against a populist ‘outsider’ who wants to upend the system and start fresh. Turkey has an autocrat who turns macroeconomic theory on its head in running its economy. South Africa is muddling through, and Russia is mostly an international pariah at the moment. Indonesia and smaller economies like Vietnam and Laos are possibly the only emerging markets that can claim to be in a similar zone as India. There’s no competition, really.

It becomes challenging to plan for India's long-term prospects because of this dichotomy of being bullish on its economy while being worried about social harmony. I mean, one day, you applaud the entrepreneurial spirit taking root in small-town India and the other day, you hear another state enacting some love jihad law. It is like that E. B. White quote:

Anyway, for the sceptics on either side, I will try to go beyond the evidence that people are good at avoiding. There are structural reasons why both these arguments about India hold. I will confess I didn’t see this scenario unfolding. Even the Ukraine war and the rise in oil price has been managed well. In continuing to buy oil from Russia (now in INR) and allying with the US on Quad, India seems to have manoeuvred the geopolitical storm well. Despite strong misgivings in some quarters (with good reasons), the key institutions (central bank, market regulators) have stayed objective and independent in their policy thinking. The bar on strong and independent institutions in emerging markets is set really low, and India seems to be scaling it easily. So, why do I harp on the risks of social harmony and overdetermined leadership? Well, the history of many emerging countries is replete with such moments of opportunity in their history. Barring a few exceptions, most have failed to capitalise on them. They didn’t get their economics wrong. Most often, they failed on political and social fronts. It reflects the barren intellectual landscape prevalent in India that we cannot acknowledge and debate these in good faith. You can only be monotheistic. There can only be one truth. Those who reject it are enemies. It’s a pity really. India Policy Watch #3: The Nature of Competitive Federalism in IndiaInsights on topical policy issues in India— Pranay Kotasthane It’s rare for semiconductors, federalism, and favouritism to appear in the same story. But the last week did blow up a political storm that combined the three. Vedanta-Foxconn signed a much-publicised Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) for a display and semiconductor fab with the Government of Gujarat. All was good. but then came the news that the consortium turned down the Maharashtra government’s reportedly superior offer, leading to accusations of the Union government having a hand in favouring Gujarat. Keeping regional and partisan politics aside, how should we parse this news? Are there frameworks to help us appreciate such events? At first, it appears encouraging that states are vying to kick off advanced manufacturing. It seems to be a perfect illustration of the merits of what is known as Competitive Federalism. States compete for investments, woo investors, and the best one “wins” the prize. Didn’t the Prime Minister say in his independence day speech that "it is the need of the hour that besides cooperative federalism, we need cooperative competitive federalism. We need competition in development”? To answer these questions, it is worthwhile to understand the “competitive federalism” rubric. This term gained prominence in public finance literature after a 1987 paper by Albert Breton titled Towards a Theory of Competitive Federalism. Crucially, he identified two preconditions for competitive federalism to be efficient. The first condition is competitive equality. This condition is similar to the logic behind affirmative action for individuals from disadvantaged communities. Healthy competition between states requires not just good umpiring but also progressive rule-making, one that does not put some states at a permanent disadvantage. In Breton’s words:

Breton identified that the responsibility for ensuring competitive equality lies squarely with the union government. In his view, two monitoring mechanisms available with the central governments are: intergovernmental grants that offset the disadvantages of certain states, and a “Council of States” that can genuinely give “salience to the provincial dimensions of public policies”. The second condition is cost-benefit appropriability. As Breton puts it:

In other words, states should be regulated by a hard budget constraint, i.e. the consequences of breaching spending limits should be significant. A moral hazard develops if states assess that the central government will bail them out in case of fiscal failure. When the budget constraints on states are of a “soft” nature, they will continue to borrow or widen their deficits, confident that other state and union governments will come to the rescue. Competitive federalism under such conditions would not be efficient. A third precondition, proposed by M Govinda Rao, is that there should be no impediments to the unrestricted mobility of factors and products across the country. This discussion of competitive federalism suggests that not all competitive federalism is good. It needs guardrails to deliver results. And the Indian experience with competitive federalism has been suboptimal as governments have violated all three preconditions to varying degrees. As a result, we are stuck in a low-level equilibrium. States compete, but on issues such as wasteful subsidies on private goods, welfare schemes, and salary structures for government employees. And when they do compete to attract investments, they do so based on spectacular tax and non-tax waivers rather than on promises of better business and law and order environments. To make India’s competitive federalism deliver, we need reforms along three dimensions:

Without some reforms along these lines, we will continue to see competitive federalism of the more harmful kind. HomeWorkReading and listening recommendations on public policy matters

* From Alexis De Tocqueville’s magisterial Democracy in America, in which he writes: “the federal system was created with the intention of combining the different advantages which result from the magnitude and the littleness of nations; and a glance at the United States of America discovers the advantages which they have derived from its adoption”. If you liked this post from Anticipating The Unintended, please spread the word. :) Our top 5 editions thus far: | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||