While excellent newsletters on specific themes within public policy already exist, this thought letter is about frameworks, mental models, and key ideas that will hopefully help you think about any public policy problem in imaginative ways. If this post was forwarded to you and you liked it, consider subscribing. It’s free. #249 Errors of CommissionIT Ministry's Advisories, EU's AI Act, and the One Nation One Election Report.Global Policy Watch: Ex-ante Tech RegulationsGlobal policy issues relevant to India— RSJRegulating AI and Big Tech are the two challenges that will test policymakers worldwide this decade. The usual tools of regulating a new science, like controlling the supply of raw materials or regulating the production or distribution of the output through laws and licensing arrangements, do not easily apply here. So, the usual mental exercise of finding a historical parallel to what we have in the form of Gen AI or Big Tech dominance over social media and then deriving regulations does not work. For instance, in terms of both opportunities and threats, you could argue nuclear power in the mid-20th century is the closest we have to what Gen AI could mean to humanity. I think that comparison isn’t exactly doing justice to the transformative power of Gen AI, but let me humour this thought for a moment. So, how did we regulate nuclear power so that we didn’t end up obliterating humanity? As yet. We built some consensus on the right usage of nuclear power and made nations commit to it. And importantly, we put significant controls on the mining and trading of raw materials and the sharing of technical know-how. The costs of producing nuclear weapons, the safety risk associated with it, and the international law on the mining and transport of radioactive materials all mean that it is expensive for a non-state actor to use nuclear power. For a rogue state, there were sanctions and restrictions that could cripple their economy. All of these restricted the threat of a dirty bomb being available to any global terrorist organisation, but it still couldn’t stop North Korea, Iran or Pakistan from building their own indigenous nuclear armament. But those blips aside, you could argue that we have done well to limit the downside of nuclear power since the mid-20th century. It has meant that we have capped its upside, too, which has given nuclear energy a bad name. But that’s for some other day. So what lessons from here can we apply to regulating Gen AI? Controlling raw materials or their distribution is difficult because everything that’s available is content for it. Limiting the spread of technical know-how is difficult because the underlying technology is already available to anyone wanting to build a similar tool. Also, Gen Al use cases are meant for end consumers, and that construct goes against the idea of any kind of non-proliferation. That leaves us with the distribution and usage of Gen AI, which can be controlled through laws, but that will beg the question of who will build and run a tech panopticon that will monitor the usage of AI at every instance. The other historical parallel is the spread of publishing technology, which meant that anyone with access to a printing press could mass-produce books or leaflets with their ideas and spread them around at a very low cost. Who will then verify whether those ideas are good or bad, whether those facts are real or fake, and how does one protect society from untested and unverified information? Stripped down to its core, it does sound similar to the threat of Gen AI at the moment, though the current threat is possibly a million times larger in scale. So, what did we do with publishing? Nothing much, really. The democratisation of publishing continued with some control over the outcome, such as banning books or laws around obscenity or libel. Over time, a falsehood in one book was countered by another, people got better at parsing propaganda from real information and some kind of equilibrium was achieved. Of course, terrible ideas spread through books, but no one blames publishing technology for it. What’s the point of this ramble, you may ask? The EU finally put together an Act to regulate AI, which was endorsed by the European Parliament this week. The Council of Ministers will approve it this summer, and over the next three years, it will come into force in stages. The EU has been a leader in tech regulations, and its data privacy act (GDPR) set the standard for regulating data around the world. With this law, the EU has again set the pace in this area. Here’s a quick summary of what I have understood from the Act. Firstly, the philosophy underpinning the Act is consumer safety, and therefore, it takes a risk-based approach to the uses of AI. So, there’s an assessment of the risk of the application of AI in different areas, and corresponding regulations have been drafted to manage those risks. This risk-based assessment means there’s a graded approach to the regulations. Riskier applications will face higher scrutiny. A quick read of the Act suggests that a significant majority of the use cases will come under the low-risk category, which will include AI to help with recommendations, nudges, and controlling spam. These will be regulated in a light touch mode, and companies will have to follow a code of conduct and voluntary self-disclosure on how they are using AI. On the other end, certain systems will be banned, including things that are dear to the EU - policing of citizens, social scoring of people based on their public behaviour and using facial recognition content from CCTV and the internet to build databases. Much of real-time facial recognition has been banned except for limited use by law enforcement with prior approvals and other controls. There is also a category called ‘high risk’ systems that aren’t banned but will be tightly regulated. These involve the usage of AI in critical infrastructure like utilities or already regulated areas like banking and healthcare. Secondly, the Act outlines an expectation of how the technical know-how will controlled and validated. The AI tools will have to be subject to risk assessment, have oversight by an ombudsman-like body, and have a log of all usage for concurrent monitoring and retrospective audits. There is a provision for EU citizens to ask why a tool made a decision the way it did for them, and the usage log and underlying logic should be able to point them to the right answers. There’s also a law around flagging of content created by chatbots or deepfakes that should disclose that they have been artificially created or manipulated. Developers of general-purpose AI will have to provide a detailed summary of text, pictures, video, and other data that will be used to train the systems. Thirdly, there’s a back door key for the government in terms of use of AI for military, defence and national security use. It has also exempted AI tools that are used for purely scientific research and innovation. These are wide ranging exceptions and can be interpreted loosely by member states to use AI in the direction they might want. Lastly, much of the work on this Act started in 2019 when Gen AI was a mere speck on the horizon. The EU regulators had to redraw their baseline and recheck their premises after the advent of ChatGPT in the last two years. This has proved to be difficult. The general-purpose AI that’s covered in the Act still looks difficult to implement. To have all model developers provide a detailed summary of the content used to train the model is like asking for the whole of the internet to be submitted for evaluation. It is also not clear what this means for the tools that are already out there and how will they comply with this. For riskier models, there are other onerous expectations like adversarial testing guidelines, reporting of incidents and regular audits. There is also a limit set for computing power to train an AI model (10 to the power of 25 flops), beyond which even more burdensome requirements will be put to ensure there’s no system risk. And, of course, there are fines associated with all of this, which could go up to 3 per cent or 7 per cent of the companies' turnover. This is a start, and many regulations seem to follow an end-user-based risk assessment approach. It will still be quite difficult to implement, but it seems to be the only way to test the waters. On another note, the Indian government came out with its own views on regulating Big Tech market power. The government is concerned about Big Tech's monopoly over the internet, and a panel set by it (CDCL) has mooted ex-ante regulations to address this. Here’s the Hindu Businessline reporting on it:

Obviously, the Big Tech companies don’t like it a bit, but they cannot say that in the open. Ex ante regulations are a bad idea in general because they act pre-emptively to control potential actions. How do you or anyone else know in advance that a technology you are working on will lead to market power skew? Conversely, the regulator can view any move by a technology company as a potential monopoly risk. We will see more action in this space. At a macro level, the question to ask is whether over the years the structures in multiple industries where technology disruptions aren’t common have turned monopolistic in nature. It will be useful to see the data on market power concentration across industries and how they have trended. I suspect we might have other issues to deal with first than regulating monopoly risks of Big Tech. Disruption, as history has shown, takes care of that nicely. India Policy Watch #1: One Nation One Election Take 3Policy issues relevant to India— Pranay KotasthaneI’ve opposed One Nation One Election (ONOE) in this newsletter twice. In 2020, I classified it as a PolicyWTF after analysing a NITI Aayog paper batting for ONOE. I felt the arguments favouring ONOE weren’t convincing enough. They felt like a veneer to justify the pain points of politicians, political parties, and star election campaigners — ‘repeated elections eat into their governance time’, ‘model code of conduct obstructs governance’ … you get the drift. So, I read the government’s High-Level Committee Report recommending a mechanism for ONOE with some interest after it was released earlier this week. Here’s what I learned from it. The report’s recommendations differ from those of the NITI Aayog paper in two notable aspects. The latter limited the definition of simultaneous elections to exclude elections to the third tier of government. In contrast, The Committee Report envisions local government elections happening within 100 days of the combined elections for the Lok Sabha and the State Assemblies. How it would ensure state governments adhere to this timeline for local body elections and maintain synchronicity isn’t made clear. The second difference is that the NITI Aayog paper envisaged caretaker governments for periods when a state assembly term fell out of sync with the election cycle. In contrast, the new proposal says that if a mid-term election occurs, the government will remain in power only until the next five-year cycle of simultaneous elections. The Committee received responses from 47 political parties, of which 15 opposed ONOE, while the rest were in favour. It also consulted some judges, election commissioners, and constitutional experts. The report literally has a photo of each of these meetings, lest you feel that it didn’t do all this work. Apparently, about 20,000 ordinary Indians have submitted their responses as well by email or website. Notably, it doesn’t seem to have engaged with the views of organisations such as the Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR), which has been at the forefront of ONOE’s opposition. The only mention of ADR is when the report perfunctorily refutes ADR’s core argument that simultaneous elections tend to favour national parties at the expense of regional ones. Apart from that, the report lays out the best-case arguments in favour of ONOE rather well. It argues that separate elections cause a waste of resources, result in policy paralysis and uncertainty, inflict a huge socio-economic burden on the nation, and develop fatigue amongst voters. There is also a simple macroeconomic study that analyses historical data to conclude that simultaneous election periods are associated with higher economic growth, lower inflation, higher investments, and improved quality of expenditure. It’s amazing the kind of evidence you can gather in favour of a decision you’ve already made. Constitutional expert Dr Subhash Kashyap finds ONOE to be compatible with the Constitution. To the opposition that ONOE might harm federalism, his response is:

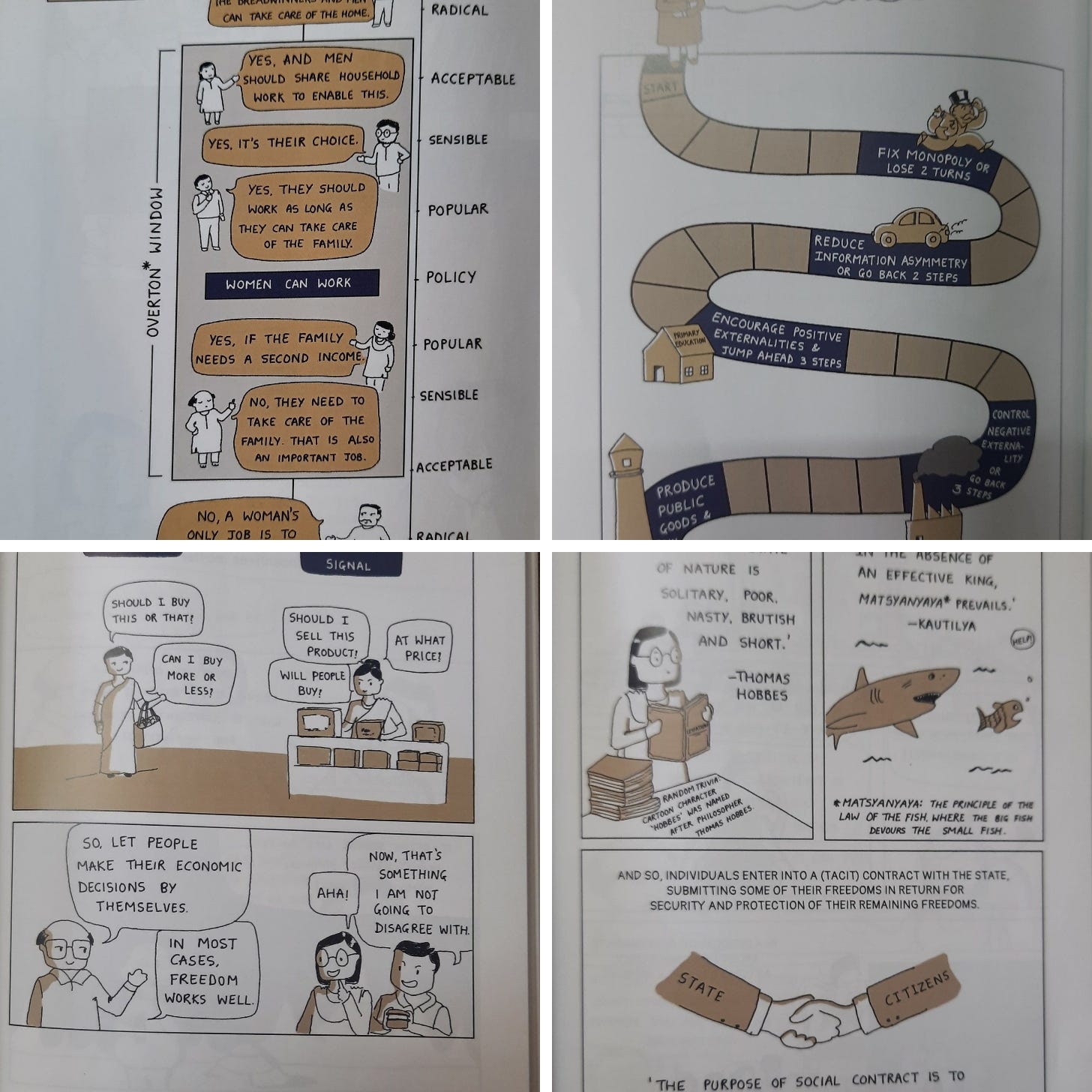

The argument that the simultaneous elections would lead to a Presidential form of government is merely “academic”, in his view. To be sure, this report does manage to assuage some concerns about the conduct of simultaneous elections, but it doesn’t try to anticipate the long-term unintended effects. There is a lot of rationalisation but little reflection. My guess is that the supporters of the move are underestimating the interconnections in a complex system. They visualise elections as a linear system, and in their assessment, the benefits of ONOE outweigh the costs. However, not only are the costs difficult to measure, but they are also concerned with some core aspects of India’s democracy, such as federalism and political parties. Perhaps it’s time to give a shot to other less disruptive measures, such as making the model code of conduct more granular, before diving headlong in the direction of ONOE. P.S.: For my arguments opposing ONOE, check out edition #226. India Policy Watch #2: The Root Cause of ‘Propose and Dispose’ AdvisoriesPolicy issues relevant to India— Pranay KotasthaneAnother week. Another u-turn by the government. The Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY) first issued an advisory on March 1, requiring platforms to seek approval before deploying AI models. The immediate trigger was Google Gemini’s response to controversial questions on the Prime Minister. Soon after, the ministry backtracked, saying that this applied only to large platforms. Finally, by March 15, better sense prevailed, and the advisory was withdrawn. Apar Gupta, in a brilliant The Hindu article, explains that there is no legal basis for these advisories and notices. He writes:

Some others were just relieved that the ministry had taken back a vaguely defined notice with significant negative effects. Nevertheless, I think both views miss a deeper point. The problem is not one of intent but one of severe lack of state capacity. I have written before that considering the economy-wide impact of its decisions, MeitY is arguably the third-most important Union ministry after Finance and Defence. The ministry is expected to make policies related to critical issues such as data protection, digital public infrastructure, semiconductors, cybersecurity, and international cooperation. Without a step jump in capacity, we can expect incompetence to show up in the policies. The new government formed after the General Election must pay special attention to MeitY's administrative capacity. That ministry’s actions will directly impact all Indians over a long time. The all-time high demand for pivotal regulations related to information technology should be matched by a surge in administrative capacity supply as well. Otherwise, we will keep seeing such instances repeat. PS: This week, MeitY is also reported to be testing a parental control app called “SafeNet”, a default app that would allow parents better control over the phones their children use. Another far-reaching decision is being made without the required capacity. HomeWorkReading and listening recommendations on public policy mattersHaven’t you purchased We, the Citizens, yet? Oh, come on. This is what a reader said over at Amazon.in - “I’m not an avid book reader. But I think this book changed me.” Apparently, even kids and young adults are reading the book (the authors didn’t expect this). Here are some of my favourite panels from the book to nudge you.  Some of my personal favourites from the book If you liked this post from Anticipating The Unintended, please spread the word. :) Our top 5 editions thus far: |