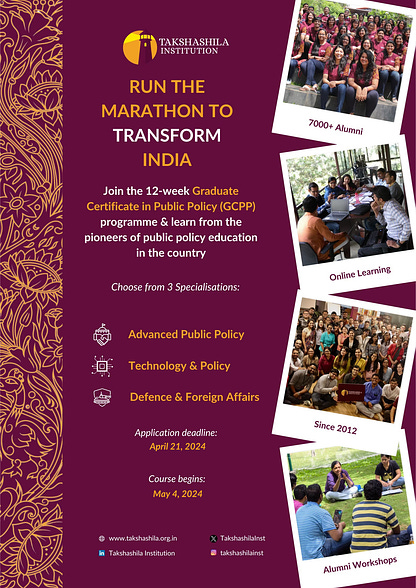

While excellent newsletters on specific themes within public policy already exist, this thought letter is about frameworks, mental models, and key ideas that will hopefully help you think about any public policy problem in imaginative ways. If this post was forwarded to you and you liked it, consider subscribing. It’s free. #252 Fair Inequality or Unfair Equality*Nozick vs Rawls in the context of the Wealth Redistribution Debate, The Curious Case of Protein Supplements, A Radical Idea for Improving University Research, and Reflections on Consumption DataCourse Advertisement: Intake for the 38th cohort of the Graduate Certificate in Public Policy Course (GCPP) has closed, but AtU readers can still apply before the course kicks off on May 4.The GCPP will equip you with policy fundamentals and connect you to over five thousand people interested in improving India’s governance. Check all details here.India Policy Watch #1: The Redistribution FallacyPolicy issues relevant to India— RSJWe’re back after that short break. Like in the case of our previous breaks, a minor threat of World War III did loom on the horizon as Iran and Israel shifted from shadowboxing to throwing a few real punches at each other during this period. And Russia seemed a few weeks away from plunging Ukraine into total darkness as it targeted its power grid till some eleventh-hour release of funds and support seemed to have averted that. Back home, reservoirs in most big cities are down to 30 per cent of their capacity, and the harsher-than-usual summer suggests a real water crisis could be on our hands in May. Through all of this, possibly, the most tepid general elections in our living memory got going last week. The incumbents are confident about their win, and the opposition hasn’t been able to mobilise public opinion to pin the government down on any specific issue that matters to voters. Is it any surprise, therefore, that the polling percentages have dropped from the previous elections so far? To be sure, behind all the swagger of the BJP poll machinery and its favourable, often fawning, media coverage, there’s a whiff of anti-incumbency in the air. Despite the charisma and the oratory of the PM, there’s a sense of fatigue that has set in on the messages. It didn’t surprise me then when I heard the PM bringing back the usual Muslim bashing in his speeches. So, we were back in the realm of discussing their fertility rates, their takeover of national resources and other paranoid fantasies that feed such conspiracy theories. It was a useful reminder that at the heart of the support for the ruling party remains the anti-Muslim brigade who love the dog whistle nature of such speeches. The need to pull out such rhetoric in an election, which seems on paper to be a foregone conclusion, suggests they can sense the lack of enthusiasm among voters, too. The Congress, on the other hand, has struggled to make sense of the signals from the ground. There is some appreciation that people aren’t as happy as they are made out to be, but what will get them to swing over and vote against the government remains a mystery to Congress strategists (if there are any). Therefore, instead of claiming its legacy of economic reforms, we have had bizarre proposals of wealth redistribution and inheritance taxes. These are the kinds of missteps that held us back through the 60s and 70s, and it took a lot of effort to make a minor shift in the Indian mindset about profits, growth and wealth creation. To abandon these as false gods and go back to the altar of gods that have repeatedly failed us and others is plain stupid. But the absence of any kind of political flair or conviction is such that the easiest solution of setting one set of citizenry (poor) against another (middle and the upper class) seems like the best. The usual question of what’s fair, intergenerational wealth distribution, and what kind of a society we should aspire for comes up while discussing these topics. We have discussed the issue of ‘fairness’ and the distribution of wealth in the context of the ‘Rawls vs. Nozick’ debate in the past. It is useful to use the framework of that debate to better understand fairness. Rawls’ seminal A Theory of Justice argued for justice as fairness (the title of a later book of his) with two key principles. First, the greatest equal liberty principle, which proposed people’s equal basic liberties should be maximised. Rawls conceived of an artificial construct called the original position - a state where each one of us has to decide on the principles of justice behind a veil of ignorance. That is, we are blind to any fact about ourselves; we are ignorant of our social position, wealth, class, or natural attributes. Behind this veil, Rawls asked how we would choose the principles of justice for society. For Rawls, the logical choice for all of us would be what he called the maximin strategy, which would maximise the conditions of those with the minimum. This gave him his second principle—that social and economic inequalities should be arranged only to provide the greatest benefits to the least advantaged. Nozick agreed with Rawls on the liberty principle. But he had a strong disagreement on the idea of maximin. For him, any distribution of wealth (or holdings as he termed it) is fair if it comes about by a just and legitimate distribution. He defined three legitimate means. First, the acquisition of an unowned property is achieved through the enterprise of a person, and this act doesn’t disadvantage anyone else. Second, a voluntary transfer of ownership between two consenting entities. And third, a redressal of a past injustice in acquiring or transferring the holdings. Anyone who has acquired wealth or holdings through these means is morally entitled to them. Any attempt by the state to redistribute it would be a serious intrusion on liberty and, therefore, unjust. So, the goal of reaching a patterned distribution of wealth had a problem at its core. Once you achieve such a delicate balance, how do you maintain it? Every random economic act from there on will disturb the balance. And such random acts will be too many for the state to control. The state will then have to constantly meddle in the lives of its citizens to redress the balance. This meddling will spiral out of control soon till the state takes over the lives of its citizens completely in a totalitarian future. For Nozick, the state can act to redistribute only with the consent of its citizens. If people voluntarily redistribute their wealth (means #2) to others and want to design a society on that principle, they are free to do so. But the state cannot impose it against their will. To me, the first point of agreement between Rawls and Nozick is critical from an Indian context - the liberty principle or the basic freedoms that must be guaranteed to every citizen. These cannot be violated, or the absence of such freedoms should not be tolerated even if doing so in some ways increases the aggregate prosperity of the society or helps the poor. Before we argue about redistribution, we must ask if we have created a society that satisfies the greatest equal liberty principle. That must be our first goal. PolicyWTF: How Pro-Business Protectionism Hurts Your HealthThis section looks at egregious public policies. Policies that make you go: WTF, Did that really happen?— Pranay KotasthaneIndian diets are notoriously protein-deficient. Don’t take my word for it. Believing anything I say on biology and nutrition is akin to asking Mumbai socialites to comment on complex public policy issues. Oh, wait, the latter happens quite commonly. Anyway, check this evidence presented by someone who knows better:

Given this reality, making Indian diets protein-adequate should be a national goal—a goal not just for the Indian State but, more importantly, for the Indian society and markets too. Thankfully, the protein-deficiency problem dawned upon us a few years ago. Soon enough, the demand for various protein supplements shot up. Markets did their thing, and now there are quite a few brands out there catering to a variety of dietary choices. But things are never that simple. A paper from the journal Medicine that has been discussed extensively in Indian media in recent weeks found that many protein brands mislabeled their protein content and also added some toxic compounds for good measure. This important study generated a lot of furore about protein supplements, with WhatsApp uncles decrying the substitution of the ‘holistic’ Indian diet for Western-style supplements. What I found entirely missing from this debate was the negative role played by the Indian State, and that’s the story I want to tell you. At least one reason we have substandard domestic protein supplements is pro-business protectionist policies. Here’s how. Once the demand for protein supplements started rising, domestic players were slow to respond, and the market was taken over by imports of dairy-based whey powders. When the market started growing, the domestic players lobbied for an increase in the customs duty on whey. They got their way. As a result, foreign brands were priced out and replaced by domestic brands. But with little competition from abroad and poor regulation at home, many of them adopted substandard production methods, and have now been exposed. And so, the money quote for me in the previously mentioned paper was actually this:

The ChronologyIndian dairy producers have long been trying to make protein supplements. A Google search got me this news report from 2009, which reports an industry giant’s imminent plans to sell whey protein powder. Fifteen years later, no such product is on the market yet. This is quite perplexing because whey is a byproduct of paneer. This whey is then processed and converted into a whey isolate, which has a high protein concentration. This isolate is what you find in the now-ubiquitous protein powder dabbas. India is the largest milk producer in the world and there’s no reason why India shouldn’t have been the world’s largest whey protein exporter. Except the State gets in the way. The dairy industry is heavily protected for various reasons. We wrote about this in the context of the opposition to Amul’s entry into Karnataka. So the dominant idea is that milk cooperatives shouldn't compete even domestically. Without competition, they have no incentive to create new products and seriously invest in building an export portfolio; their preference is merely import substitution. Thus, it isn’t surprising that they got the government to increase the basic customs duties on whey powders to 40 per cent. Now you know why that imported brand of protein powder dabba costs so much! Domestic players weren’t happy even with this; they wanted the customs duty hiked further to 60 per cent. This is a familiar pattern in many industries. Domestic incumbents are only concerned with cornering the domestic market. They cry hoarse when imports increase, and are able to price out imported goods by getting tariffs raised using the ‘infant industry’ argument. Why bother about exports when you can corner a rigged domestic market instead? Faced with no external competition, their product quality declines. Eventually, the market settles into a low-level equilibrium, one in which consumers have fewer choices and domestic producers don’t upgrade. The flip side of this pro-business protectionism is that the State is failing at what it should actually be doing. The Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) needs a lot more capacity to enforce food safety regulations. Apart from protein supplements, the recent case of Singapore and Hong Kong banning two popular Indian spice brands due to quality concerns is another reminder of India’s poor food safety regulation enforcement. The Indian State, yet again, is omniabsent — busy doing what it mustn’t while not doing what it should. P.S.: Don’t even get me started on the State’s role in making Indian diets protein-deficient. Policies such as the Minimum Support Price for cereals have increased their production and consumption, resulting in a carb-rich diet that has created several public health challenges. India Policy Watch #2: The Consumption QuestionPolicy issues relevant to India— RSJHow robust is the famed India domestic consumption story? It is becoming difficult to figure this out. Take Q3 FY 24 (Oct-Dec 2023) numbers. GDP grew by 8.4 percent which was significantly above the market estimates. The Chief Economic Advisor, V Anantha Nageswaran, while commenting on it suggested a structural transformation in the economy:

If you looked at the sector-wise breakup, it did seem so. Manufacturing and construction grew at double-digit rates while consumption was tepid at 3.5 per cent. Domestic consumption and exports have been the mainstay of economic growth in the last decade when the gross fixed capital formation has been negligible. So, has the consumption engine stalled? I keep an eye on the results of the FMCG companies to get a sense of consumption trends and demand. The commentary during the last couple of quarters hasn’t been great. Take the Q4 results Hindustan Unilever, the bellwether domestic consumption stock, announced last week. Revenues were flat, profits were down 6 percent and the outlook for the next year wasn’t any different. While the company continues to talk up the India story in business conclaves, its business projections don’t match the story. And this quarter wasn’t a one-off. This has been the trend for more than a year now. In fact, it is a question that can be asked of the overall FMCG sector which has grown at 3 percent and 1.5 percent in FY 22 and FY 23. If the economy is doing so well, where is the volume growth in the consumer goods sector? What can explain this? I see three reasons for this. First, there is clearly a shift towards investment in the economy post-COVID-19, with its share of GDP rising to almost 35 per cent from less than 30 per cent in 2020. If you look at the results of the banks and NBFCs, the credit growth has been 25+ per cent in the last two years for the SMEs, small business and sole proprietorships segment. Even the home, auto and personal loans segments have grown at 2x the GDP growth. The Investment growth curve, therefore, is back to the pre-pandemic level. That is, it has taken the pandemic years in its stride and reached where it should have been had there been no pandemic. Correspondingly, the consumption growth has lagged. Second, as the SMEs and small business owners build back after COVID-19 and avail credit to grow, the kind of consumption shift we saw during COVID-19 to larger and more formal companies is starting to unwind. There are smaller, nimbler players well-funded who are eating away the market share of FMCG companies, especially beauty and personal care businesses. And the post-Covid recovery by smaller players in food (bakeries, restaurants), retail stores and the informal sector has meant the shift to formalisation has stalled or even turned back. These players have regained their market share lost during the pandemic and that’s showing up on the balance sheets of large, listed FMCG companies. The overall impact of this ‘de-formalisation’ is difficult to read at this time but my sense is the lead indicator of credit growth in this sector will play out over the next few years. Lastly, at a macro level, while we have not yet reached our expected pre-pandemic trajectory of GDP growth (that is, the recovery post-pandemic hasn’t yet coincided with the trendline we were on before), we continue to have more than 12 million join labour force every year. In a way, we will have this slack for some time till GDP reaches the pre-pandemic trajectory. This means we will continue to see inequality in consumption between the cream of the households (top 10 per cent) and the bottom 90 per cent. This is what is playing out now as you see premium consumption categories doing well on volumes while the overall growth remains sluggish. There is also the matter of commodity price increases in the past 3 years which is mentioned often in the commentary of FMCG companies. These input price increases have hurt margins and offered limited room for innovation or marketing spending to generate demand. This is also a trend that’s likely to continue in FY 25. Bottom line, we will continue to see the divergence of a 7+ percent GDP growth but with consumption coming in at less than 4 per cent growth for the next couple of years. I don’t think it is a result of structural transformation of the economy. It is just the way things have fallen post-pandemic. The divergence, especially sluggish growth in domestic consumption is a bit of a worry but my guess is it shouldn’t last longer than two years. PolicyFTW: Improving Higher Education at the Margin?This section looks at surprisingly sane policies- Pranay KotasthaneNot sure if you’ve been observing, but the University Grants Commission (UGC) has been making some interesting moves lately. In July 2023, it allowed universities to recruit entry-level assistant professors even if they didn’t have a PhD, as long as they had cleared the qualifying examination. Earlier last week, it announced that students with four-year undergraduate degrees can directly appear for the qualifying exam and pursue PhD in any discipline, without a master’s degree. I classify this latest attempt to increase doctoral degree intake as a conditional policy win. A win because it might reduce the unnecessary hoops that students have to jump through in order to make a career in academia. The times have changed, and there’s no reason to retain an industrial-age doctorate system. But if it does result in more students applying for doctorate programmes, who will be their PhD guides? Is there enough slack in the system to absorb more students without a decline in quality? I don’t suppose that’s the case. That’s why the policy win is conditional on an important factor: an increased number of good-quality PhD opportunities and guides. Given that India does poorly in terms of good-quality research universities, there’s one way of getting this done. Merge the 37 national laboratories under the Council of Scientific & Industrial Research (CSIR) with existing universities or make a portion of their government grants conditional on them producing PhDs. After all, government funding for R&D is justified on the grounds of “positive externality”, and a key component of this externality must be to equip the next generation of researchers. What do you make of it? HomeWorkReading and listening recommendations on public policy matters

* This phrase comes from a paper, Why people prefer unequal societies, by Starmans, Sheskin, and Bloom, which argues that “People prefer fair distributions, not equal ones” and “humans naturally favour fair distributions, not equal ones, and that when fairness and equality clash, people prefer fair inequality over unfair equality” If you liked this post from Anticipating The Unintended, please spread the word. :) Our top 5 editions thus far: |