While excellent newsletters on specific themes within public policy already exist, this thought letter is about frameworks, mental models, and key ideas that will hopefully help you think about any public policy problem in imaginative ways. Audio narration by Ad-Auris. If this post was forwarded to you and you liked it, consider subscribing. It’s free.

Programming Note: Anticipating The Unintended will be on a 3 week break. We will send you select pieces from our archives during this period. Normal service will resume from May 15. India Policy Watch #1: Hindi Hain Hum...Insights on burning policy issues in India- RSJ There’s that oft-quoted line of sociolinguist Max Weinreich that goes ‘a language is a dialect with an army and navy’. Like many facetious remarks, it isn’t scientific, but it sounds great. Also, there’s a kernel of truth in it. The only reason a particular dialect races ahead of others and transcends a threshold to turn into a language is when it is backed by political patronage and the power of the state. Examples abound. The version of Hindi that’s official in India today, for instance, wasn’t the kind that was spoken by anyone even two hundred years ago. Many in India find this hard to believe. But it isn’t too difficult to prove. Read any text or literature that was popular in north India before the 19th century, and you will find the language bears no similarity to the official Hindi of today. The great texts of 16th century India will help you with this. Ramacharitmanas by Tulsidas was written in Awadhi, Surdas used Brij bhasha and Guru Granth Sahib is an eclectic mix of languages ranging from Sindhi, Lahnda, Persian and Brij bhasha. The first works that bear a strong resemblance to the Hindi of today appeared in 1870-80s when Bharatendu sought to popularise a combination of Awadhi and Brij with a generous sprinkling of tatsam words from Sanskrit while stripping away the Urdu words. This project gained political support in the late 19th century when there was Hindu revivalism in the air. The decimation of the Mughal empire was complete and with it went the state patronage of Farsi and Urdu. There was desire then to find a purified version of the Hindustani language that preceded the Delhi Sultanate. Bharatendu filled this gap and his efforts were ably supported by the Raja of Benaras and the Kashi Dharma Sabha. Post-independence, this version of Hindi got its ‘army and navy’ with the might of the state behind it. And it turned into a language. Quite appropriately, it was called the ‘rajbhasha’; the language of administration or the language of power. What’s the point of this bit of historicising? Well, here’s the press release from the 37th meeting of the Parliamentary Official Language Committee held last week that was presided over by the Union Home Minister (HM):

The usual furore followed. This isn’t the first time the HM has made this sort of an appeal. Every year on the occasion of Hindi Diwas there’s a similar pitch about Hindi. The usual benefits are stated. That we need a ‘link’ language for India and Hindi is best suited for it. Not English. That’s a foreign tongue and the language of our colonial humiliation. We will be somehow more united if we all speak in Hindi. It will foster a feeling of togetherness among Indians. Or that’s what I have understood as the benefits of this push. I’m sceptical of the unity argument because it makes limited sense. There are better ways of fostering unity than asking people to privilege a specific language in a country that has as many languages with long histories as India. In fact, it will likely lead to more divisions and strife. On the other hand, the ‘link’ language argument has some merit. What common language should people use to converse with each other when they are native speakers of languages as diverse as Punjabi, Bangla and Tamizh? It is a good question. But there’s no need to find a planned answer to this question. This is a question that was possibly as relevant during the times of Ashoka, Chandragupta, Akbar and Lord Canning, as it is today. The courts of those times used Pali, Persian or English as the official language of the state. But that didn’t mean these became the languages of the masses. People developed their own dialects and languages that worked for them to communicate with one another. A language can have its army and navy but those won’t make it the ‘link’ language. Because the adoption of a language and its usage in a society is the best example of spontaneous order at play. Spontaneous orders aren’t planned by anyone. There is no intentional coordination of actions by any external agent. Every participant acts in their individual best interest for their own objectives. However, these individual actions aggregate into a pattern of their own. It is the ‘unintended order of intentional action’ that emerges on its own and it adapts to the ongoing changes. Language is a classic example of this. No one individual could have designed it. There’s no central design of associating a sound with an object or an emotion. It evolves by the attempt of separate individuals trying to solve the problem of communicating with one another. The sounds that are easy to use and adopted by most individuals evolve into the lingua franca of the community. Language is ‘the result of human action, but not of human design’. As the language becomes more widely adopted, there are attempts to formalise its structure and syntax. As these structures become more rigid and people are forced to use a language in only a certain way, it begins losing its flexibility and its utility. People find a more flexible mode of communication and a new order emerges. A new language of the people is born. This is how Latin, Sanskrit, and Persian continued to be the languages of the church, court or the temples but the continuing rigidity of their grammar and their top-down imposition on people led to their decline. Spontaneous order killed them off. If the people feel the need for a link language, they will find one through the millions of everyday transactions that they undertake. In India, this could be Hindi, English or some motley mix of tongues that will work for people. That’s the direction we will head into as we find more reasons for domestic mobility and interactions. Any attempt to centrally plan for greater usage of an official language is therefore futile. It takes away time and attention of the state to focus on more real issues. And it leads to divisive politics over the imposition of Hindi over regional languages. World history is rife with examples of civil unrest and strife because of such impositions. These are unnecessary distractions that we can live without. Or maybe that’s the point of all this. India Policy Watch #2: …Watan Hai Hindustan HamaraInsights on burning policy issues in India- RSJ I wrote a couple of weeks back about ‘Nehru: The Debates that Defined India’ by Adeel Hussain and Tripurdaman Singh. The book examines the key debates Nehru had with four of his peers, namely, Iqbal, Jinnah, Patel and S.P. Mookerjee, on questions of religion, foreign policy and civil liberties. The authors set up the historical context for each debate and why it was critical at that juncture and then reproduce the letters, columns, or speeches of the protagonists. I have picked up the debate between Nehru and Iqbal this week. Iqbal and Nehru were temperamentally similar with both having studied at Cambridge and trained as barristers. They were steeped in enlightenment philosophy, had a taste for western literature and were socialists by instinct. Where they differed sharply was in their confidence in the transplanting of such values into Indian soil. They came at the idea of nationalism in a subcontinent as diverse as India with widely divergent first principles. Nehru believed in a kind of inclusive nationalism where people would voluntarily shed those parts of their identity that separated them from others while retaining the core somehow. This was a difficult notion to explain, let alone implement. For Nehru, the state was to be secular with joint electorates, a reformed social code for Hindus and Muslims while simultaneously letting people practise their religions without any other interferences. Iqbal thought this was an impossible task. This utopian ideal of fusing the different communities into a single nation was fraught with disappointing everyone equally. The state would tread into areas of citizens’ lives that it had no business to be in. Democracy where numbers matter would make this risky for the minorities. There was a need to think of nationalism while protecting the identities of communities and giving them their space to breathe. Trying to hoist a unitary, majoritarian version of democracy without thinking about proportional or specific representation would lead to a situation where ‘the country will have to be redistributed on the basis of religious, historical and cultural affinities.’ Iqbal thought Nehru wasn’t thinking of the long term where those holding the power of the state would be different from them. Needless to say, this idea itself was abhorrent to Nehru. He wrote a long response to Iqbal from the Almora district jail where he has housed in 1935. Titled ‘Orthodox of All Religions, Unite’, it gives us a window into Nehru’s thoughts on the consequences of the nationalism advocated by Iqbal. Reading it 87 years later is clarifying. It is a debate between an idealist who wants to ‘will’ a perfect society. Against whom is pitted a realist who knows this is futile and the best course is to set up a system that’s in sync with how the society works. This would then be supplemented by a code or set of guidelines that would provide the incentives for right behaviours by those in power than force a philosophy down their throats. I have quoted parts of Nehru’s response below. It is a fascinating blend of idealism and naïveté which characterised the man:

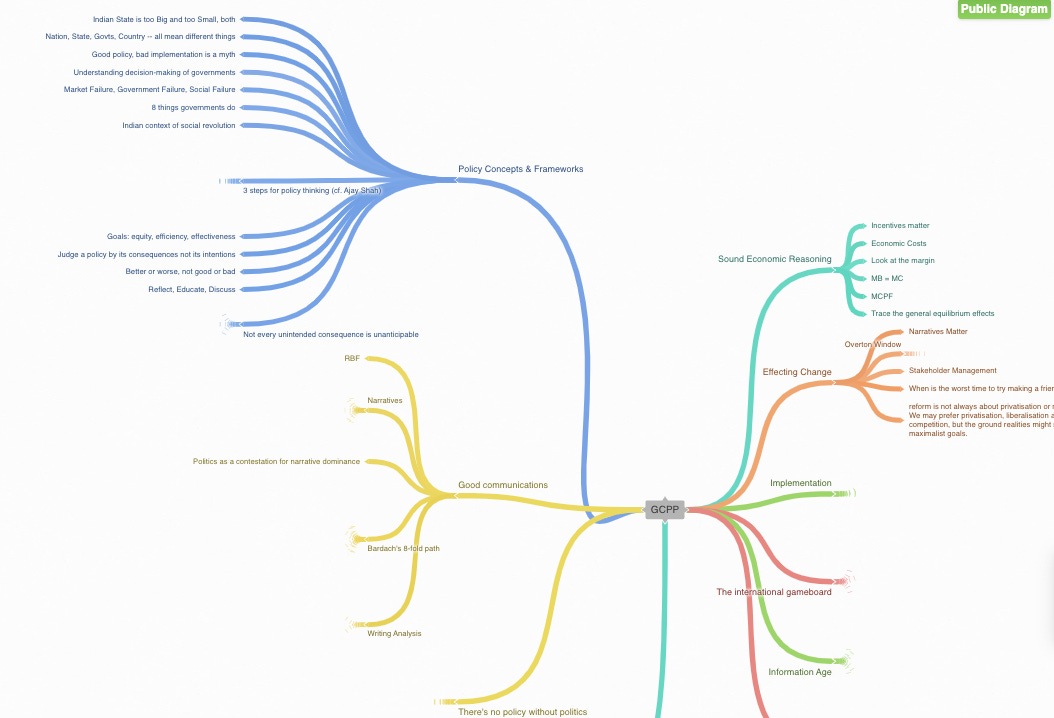

Advertisement: If you enjoy the themes we discuss in this newsletter, consider taking up Takshashila’s Graduate Certificate in Public Policy course. Intake for the next cohort closes next week. 12-weeks, fully online, designed with working professionals in mind, and most importantly, guaranteed fun and learning. This mindmap from the last session of every cohort gives a good idea about what students learn in the course. Do not miss it.Global Policy Watch: Why have Political Parties by Women and for Women Not been Successful Electorally?Indian perspectives on global events— Pranay Kotasthane On International Women's Day last month, I went back to a question that has perplexed me for a long time: what explains the electoral insignificance of political parties by women and for women? We see in India that political tribes—and parties—get created along many different identitarian dimensions. The proliferation of political parties backed by a small and reliable electoral base is quite common in India. And yet, we don’t see political parties created on the basis of gender. Most probably, there are structural reasons why this hasn’t happened yet in a society prejudiced against women. However, India is not an exception in this case. Women’s political parties have been electorally insignificant even in Western Europe and Scandinavia. What gives? In this article, I am sharing a few notes from my ongoing search. The Quillette asked this question in the UK context. Louise Perry's article has interesting insights. For instance, she writes that political tribes form when there is little interaction across tribes, which is not possible with gender as an identity variable. In her words,

Of course, Perry also highlights that feminist parties are not the only way to reduce gender discrimination.

Further, Perry cites more studies to highlight that gender does not impact voting behaviour by much.

In another article, Corwell-Meyers et al make an important distinction: not all women’s political parties are feminist parties.

The authors conclude with a more considerate view of women's political parties and argue that there are some second-order benefits of such organisations, such as:

That’s all I’ve managed to gather on this topic thus far. If you have any helpful links or articles on this topic, do leave a comment. HomeWorkReading and listening recommendations on public policy matters

If you liked this post from Anticipating The Unintended, please spread the word. :) Our top 5 editions thus far: |